ENGLISH

ENGLISH

INTERVIEW

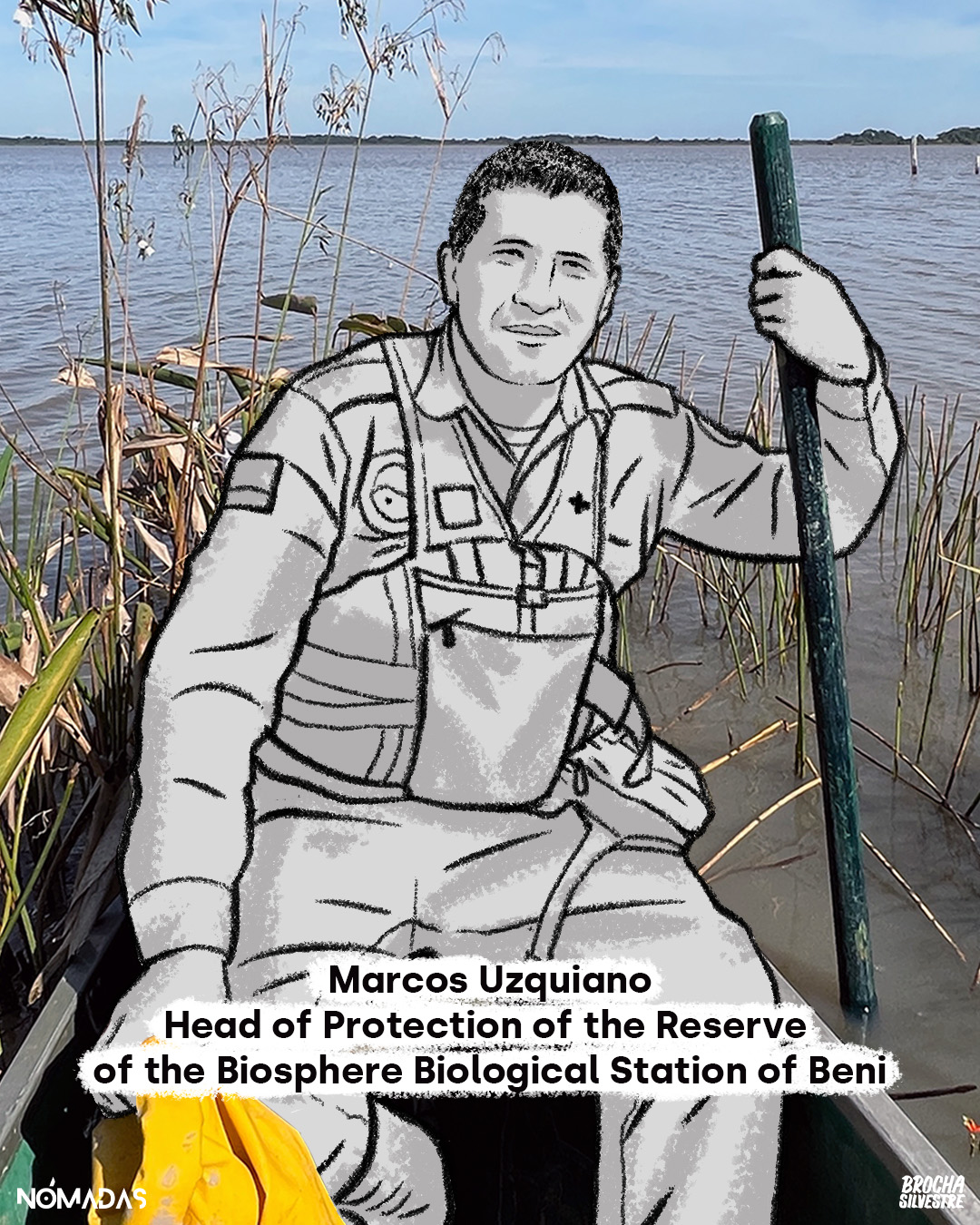

Marcos Uzquiano, the brave Head of Protection at the Beni Biological Station Biosphere Reserve, faces a dangerous enemy: illegal miners who threaten the lives of park rangers and the biodiversity of Madidi, the most biodiverse protected area in the world. In this interview, Marcos reveals the dark secrets behind his relentless struggle to protect the forest and how the miners pressured the Bolivian government to relocate him to a place where he would make «less noise.»

August 21th, 2023

Roberto Navia Gabriel

Journalist

-How much does it cost to protect the forest?

-That’s a good question. However, in terms of effort and resources, I think it is invaluable. There is the effort primarily made by the park rangers, the effort of the State, which is complemented by social and community efforts. So, determining an economic cost is difficult, almost impossible, because it is a very complex task that involves many factors, not just economic, operational, and technical aspects, but above all, it is a commitment.

-You have worked in several protected areas. You have become an icon in the defense of forests, even risking your life. What does this task entail, and what enemies have you encountered?

-I have had the privilege of serving in the National Service of Protected Areas. I had the opportunity to work for most of my career in the Madidi National Park, and I come from there. I have also provided support through exchanges in the Apolobamba Natural Integrated Management Area (ANMI) in my early years as a park ranger, then I became the Head of Protection, and also acted as interim director for a month. The TIPNIS has also been one of the most important spaces where I have been able to carry out my duties.

Currently, I have been working at the Beni Biological Station and Biosphere Reserve for about two years. In the 20 years of experience in the National Service of Protected Areas, I have had to compromise my physical integrity many times, as well as that of my family and, obviously, the entire team of park rangers, to safeguard the territorial integrity of protected areas.

This means having a high level of commitment but also facing threats and insecurity. You become aware of what your life and job stability as personnel in protected areas can be like. I believe that this situation is of great concern to park rangers in our country at the moment, as pressures and threats increase, and this is very complex because the state does not confront it.

This makes it even more challenging for park rangers as it involves carrying out the work without sufficient economic resources, often with limited human resources, meaning a small number of hired park rangers.

The level of threats is growing every day, such as deforestation, wildfires, mining, logging, and wildlife trafficking. Essentially, it becomes a titanic task that we perform. For those of us committed to this fight and defense, it is our life, part of our very existence. The work of park rangers at the national level is key and very important, driven by this commitment and passion for nature and life, which is the driving force that keeps us going.

Being a nature defender means having a high level of commitment, but also facing threats and insecurity. You realize what your life and job stability as protected area personnel can be like.

-How many times have you been in danger for defending the forest?

-Like my colleagues, I have been verbally and physically assaulted, received threats for the work we do, and felt pressure not only from offenders, from people who threaten our biodiversity, but also political pressure from sectors aligned with certain allies of the current governments. Basically, this becomes one of the most critical issues we face.

What park rangers least expect is to be pressured and threatened from within the state institutions, which should be guaranteeing the care and protection of those who protect and conserve biodiversity. But many times, this has turned against us, or they have been instruments to pressure those opposed to protected areas and to exert pressure against defenders of nature.

I could tell multiple stories, but time would not be enough. I simply appeal to the State and society. If the State thinks that park rangers are solely responsible for protecting our forests, they are greatly mistaken. This demands joint action, with civil society joining in the titanic task of park rangers in Bolivia and, obviously, working together with our own state institutions.

-Can you recount an event where you were in danger?

-The latest threat I faced was from the mining sector when I was in Madidi National Park. I received threats to my physical integrity through messages on Messenger and WhatsApp, pressure, insults, and even smear campaigns on social media. Many times, I was on the verge of being physically attacked or subjected to strong pressure at the headquarters of a federation of social organizations affiliated with these activities, where you feel a lot of pressure from the very people you believe you are protecting the common good for. You feel pressure from community leaders.

It has been terrible to face that wave of threats, especially when I was in Madidi National Park due to the mining sectors. They have threatened to end my life and harm the park rangers. Essentially, they have managed to exert some pressure because they threatened to get rid of us through the State institutions. They said they would make us be dismissed from our jobs or be relocated elsewhere, and to some extent, they have succeeded.

But I believe our commitment is strong enough to keep standing, regardless of where we are. We will continue to support and defend our protected areas. Now, I am at the Beni Biological Station, a marvelous protected area, and from here, I am also exercising that defense, that fight, for the rest of the protected areas in the country.

-In the end, did the miners pressure the government to relocate you from Madidi?

-It has been that way. They pressured through statements, resolutions, and even threatened to block roads, take over offices and camps, and they continue to threaten to prevent me from returning to Madidi National Park. I am sure that if such a thing happens, they will rise and pressure the government. They have done it with other authorities where they have blocked roads to confront anyone who threatens or undermines their interests. This is a very critical situation.

Uzquiano, defender of life.

– Are they like a state within a state?

-Absolutely. They are a very powerful force because they have a lot of influence in political, economic, and social realms within the communities. Mining in this context has terribly affected an important protected area like Madidi. I’ll allow myself to refer to this place because I have devoted a large part of my work there, and I consider that Madidi is currently critically wounded, where the mining sector has taken complete control.

Park rangers in the Apolo sector no longer have the capacity to exercise full control because they have been completely encroached upon and violated in their functions. Unfortunately, the State institutions, such as the Police and the Army, do not contribute to enabling park rangers to perform their duties properly. It is a critical situation they are facing, and I feel that the State does not have the capacity to provide guarantees or protection to Madidi, which is the most biodiverse protected area in the world. So, I ask myself, what are we going to protect as a country?

– Are the miners operating within the Madidi protected area?

-Absolutely. They are in the Apolo sector, where there are a significant number of companies operating under the name of mining cooperatives, and behind these cooperatives, there are foreign capital, including Chinese. So, it is basically an out-of-control situation.

Now, the park ranger has to ask for «permission or authorization» to carry out their work within the protected areas. In Madidi National Park, many administrative processes have been initiated. I highlight the great effort made by park rangers, but unfortunately, these efforts are no longer sufficient to guarantee Madidi’s protection. What do I mean by that? The administrative processes and actions have remained just that, administrative processes. They have not been effective in stopping the threat or achieving any environmental adaptation of these activities that are being carried out without any kind of authorization, environmental license, or mitigation measures to alleviate the impacts they are causing.

– And are these cooperatives legal or illegal?

-To a miner, being legal means having a concession within the protected area. For me, they are illegal because they do not comply with environmental regulations or the permit to operate within a National Park, which are the requirements mandated by the State’s laws. Since they do not meet these established requirements, they are simply illegal. You can’t be partially legal; being legal means complying with all the requirements. If you don’t meet one of them, as is the case here with the environmental license or authorization from the National Service of Protected Areas (SERNAP), then you are illegal.

– In the heart of the Amazon, in the most biodiverse area in the world, they are in danger of death. I understand that SERNAP initiated an internal process against you

-Yes, I have indeed undergone an administrative process and an abrupt transfer that resulted in a change in my position. They sent me to the Beni Biological Station, and this transfer was in response to pressure from the mining sector. There is no doubt about that for me. However, they informed me that it was for my safety and to strengthen the Beni Biological Station Biosphere Reserve, but the way they did it completely met the demands of the mining sector.

They also initiated an internal administrative process, a disciplinary process, for a supposed offense I committed in 2020. It’s as if you play a game three years ago, and suddenly a referee comes and shows you a red card, and you ask why, for a match you played four years ago.

In my defense, I submitted evidence to the higher hierarchical level, but they did not consider my arguments, evidence, or the legal documents we presented. They confirmed the disciplinary action based solely on a report from a head of protection from another protected area. On this basis, they proceeded with the process and imposed a 20% salary deduction on me. In response, I filed a constitutional remedy, and I hope that justice will eventually give me the opportunity to defend myself at that level.

Like my colleagues, I have been verbally and physically assaulted, received threats for the work we do, we have felt that pressure not only from offenders but also from people who pose a threat to our biodiversity…

– Did you ever consider resigning, saying, «This is too much, I should take a different path»?

-At some point, I did consider resigning, but I took some time to reflect, and I also received advice not to do it because it would show weakness and that I was fleeing from that supposed responsibility.

– Why do the miners have so much power?

-I think the issue is economic; there is a lot of political influence. They possess a great social force, with strong support from communities, individuals, cooperatives, and families connected to mining activities. With the power they have, they exert pressure on any government in office. So, any government will always give in because what matters to them is having support and votes. There is also a lot of economic power or signs of corruption being managed somewhere, as there is no other way to understand it. According to information from the park rangers, now the miners choose which park ranger they want to carry out inspections. For me, that’s very strange; it’s like a criminal choosing which police officer will patrol, and that’s very delicate.

I hope it’s just suspicions, but if any of these cases were confirmed, it would be tragic for Madidi and for all the people who believe that Bolivia has a strong Protected Areas system, and unfortunately, due to attitudes like this, everything that has been built over many years could be undermined.

– You devote your life to this like a calling, and you are married. How does this affect your family life?

-Well, without a doubt, I believe that’s one of the challenging aspects of being a park ranger. This commitment to protecting the Protected Areas means that you live far away from your family. Obviously, it’s our decision to do so, to take on this responsibility and work in this way. The family understands, comprehends, and supports it, but that distance also cools any relationship, anywhere in the world.

It’s sad; many park rangers have ended up separating from their families. It’s a very complex and delicate issue, but in the end, we, as guardians of nature, have chosen this path. It’s a decision, a life’s calling, and I think it will be very difficult for us to change it.

This interview is part of the Special: Bolivia’s Invisible Amazon and its guardians who do not give up, carried out by Revista Nómadas, with the support of the Amazon Rainforest Journalism Fund in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

STAFF:

DIRECTOR: Roberto Navia. PRODUCTION MANAGER: Karina Segovia. PHOTOGRAPHS: Karina Segovia, Lisa Mirella Corti. SOUND PRODUCTION AND POST-PRODUCTION: Andrés Navia. ILLUSTRATIONS AND INFOGRAPHICS: Brocha Silvestre. SOCIAL MEDIA EDITOR: Lisa Mirella Corti. WEB DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT: Richard Osinaga. COLLABORATION: Manuel Seoane, Diego Adriázola y Daniel Coimbra.

COPYRIGHT 2023

Te contamos desde el interior de los escenarios de la realidad, iluminados por el faro de la agenda propia, el texto bien labrado y la riqueza poética del audiovisual y de la narrativa sonora, combinaciones perfectas para sentir el corazón del medioambiente y de los anónimos del Planeta.