ENGLISH

ENGLISH

The waters of Tuichi connect with Madidi – Credit: Lisa Mirella.

August 21th, 2023

The Tuichi River is no ordinary river; its powerful and untamed waters flow from the Andes to the Amazon, offering a journey that allows you to witness the grandeur of a roaring river. Its waters form the lifeblood of Madidi National Park, the territory with the highest biodiversity in the world, and it is also home to guardians with a river’s soul, working to keep the flow of life that gave them birth healthy.

Lisa Mirella Corti

Journalist

Jhorlan never imagined he would lead an eco-lodge, especially after being a petroleum engineer. But today, he faces the greatest challenge of his life – to continue the legacy his father Martín built, working to conserve and respect nature. Jhorlan is now the president of the Chalalan board, a historic eco-lodge built by indigenous people in the dense Bolivian Amazon forest within Madidi National Park, a green universe covering nearly 2 million hectares, known for being the most biodiverse region on Earth.

With an extraordinary biological richness and diverse ecosystems, it houses 1,830 confirmed vertebrate species, 5,535 plant species, and 1,809 butterfly species and subspecies, making it the refuge with the highest diversity of confirmed wildlife known to science. Madidi is home to 3% of the world’s higher plants, 3.7% of vertebrates, and nearly 10% of the world’s bird species. This Amazonian fragment is vital for the balance of the entire planet.

In Madidi National Park and the Integrated Management Natural Area Madidi (PNANMI Madidi), 31 communities of Tacana, Leco, and Quechua origins reside, with a population of about 4,000 inhabitants. The Madidi area overlaps entirely with the Communal Territories of Origin (TCO) Uchupiamonas and partially with TCO Tacana I, Lecos de Apolo, and Lecos de Larecaja. It is in this territory that its historical guardians confront the enemies threatening their living space.

Deep in the jungle, along the Tuichi River, the main tributary of Madidi, the inhabitants of the indigenous village of San José de Uchupiamonas decided to embrace community tourism as a development model. A brave endeavor in Bolivia, a South American country rich in biodiversity, but with plenty of politicians with poor ideas who come to power with a predatory view of nature, demonstrating this for decades with their hunger for extracting anything they can from the land to fill their pockets, leaving long-lasting wounds in the territories without remorse.

It was not an easy task for the people of San José to embrace community tourism. The lack of attention from the central government in health, education, and basic services led to the migration of many families in search of better living conditions in the 1980s.

«The town was becoming empty,» recalls Jhorlan Laura Quetegüari, with almond-shaped eyes, a youthful face, and a kind smile, describing what life was like when he was a child in his village, San José de Uchupiamonas, before Chalalan existed, the first eco-lodge in the area that became an inspiration, an icon, and a catalyst for other ventures, equally managed by indigenous communities, to flourish along the banks of the Tuichi River.

A chain of events involving the disappearance of adventurers in the jungle, a book, much sweat, and collective effort to prevent their people from migrating led the entire community to question how to avoid the disappearance of their village and create alternative dignified employment opportunities.

In the 1980s, the Tuichi River, the main artery and channel that connects the town of San José de Uchupiamonas to the world, was still an unknown, invisible, and untamed river. Its fast waters originate at the top of the Andes, in the Apolobamba mountain range, the high zone of the Madidi mountains. With a course of 265 kilometers, the Tuichi is no ordinary river; it connects the Andes with the Amazon, its waters flow like a liquid serpent through various ecosystems, transforming the landscape as they glide along. The snow-capped peaks in the distance disappear, and lush, green mountains covered with trees of every imaginable shade start to appear. In the heart of the tropical jungle, its waters flow through the impressive Bala Canyon, as if performing a ritual to become the mighty Beni River, continuing its journey beyond Bolivia’s borders as the Madeira River, becoming one of the most important tributaries feeding the world’s longest river: the Amazon.

Everything changed for the Tuichi River and the communities of Madidi in 1990 when Yossi Ghinsberg, an adventurous Israeli, fell off his raft while navigating the river and was swallowed by the forest for 21 days. After a physical and mental battle with the elements of nature, filled with bites, hunger, and exhaustion, he was rescued by locals who, since then, he considers his brothers. Jossi’s survival adventure was narrated in his book «Back from Tuichi,» becoming a bestseller and catapulting the Tuichi River as an icon of daring adventure symbolizing the Amazon. His story sparked a wave of adventurers eager to reach where Jossi had been, flooding the Tuichi with tourism.

Jossi is now part of Chalalan’s history. He was one of the driving forces in the 1990s behind the idea of an ecological lodge that would improve the quality of life for locals through dignified jobs and promote harmonious tourism aligned with the ancestral values of caring for their territory. The constant threat and intrusion of loggers in the Chalalan lagoon area, within the Tuichi Valley, led the residents of San José to strategically consider the location of the eco-lodge and work alongside Jossi, their new brother, to seek international financing. With a commitment to conserve the jungle, they obtained funding from the Inter-American Development Bank for a pilot project. The Chalalan enterprise was established in 1992, before the creation of the young Madidi National Park in 1995, and despite its ups and downs, over more than 20 years of operation, the most remarkable aspect of this venture is the 100% indigenous governance and collective ownership by the entire community of San José de Uchupiamonas. All other tourism projects that later emerged along the banks of the Tuichi River are children of Chalalan, fruits of the labor of people like Jhorlan’s father, Professor Martin Laura, a founding partner of Chalalan and an environmental activist for nature conservation.

For Jhorlan, taking over the company is a challenge for himself, but he also aims to fulfill his father’s dream – to preserve the limited Amazonian space they have in Bolivia. He has faith and confidence in sustainable tourism, seeing it as the only strategy that can effectively stop the indiscriminate exploitation of the resources provided by the forest where his ancestors were born.

Wilmar Janco was born in the heart of the Bolivian Amazon on the banks of the Tuichi River. His family lived deep in the jungle, weaving jatata palm leaves for house roofs before the tourism boom, before what is now known as Madidi National Park even existed. Tuichi represents his essence, his life, and his roots, but it also symbolizes his future, his way of making a living, preserving his indigenous culture, and building a future for his children. Wilmar comes from Villa Alcira, an indigenous community of Tacana origin that is part of the Indigenous Council of the Tacana People (CIPTA), one of the communities that share the river.

He worked as a park ranger in Madidi for 10 years, exploring every corner of the dense forest, which allowed him to better understand the protected area and, above all, its importance for conservation. Observing other successful ecotourism projects in the area motivated him to venture into tourism activities and create opportunities for employment for families in the communities. All of this, combined with his desire to contribute to the conservation of his indigenous territory guided by his ancestral knowledge of the jungle, wildlife, and traditional medicine.

Today, Wilmar is the general manager of the Mashaquipe tourism enterprise, a fusion of two words: «Masha,» of Tacana origin, and «Quipe,» of Quechua origin, which together mean «Many things in one trip.» Mashaquipe Eco Tours started its operations in 2009, owned by a group of Tacana indigenous families, with the aim of offering ecotourism activities and experiential tourism while serving as a means of subsistence and supporting the conservation of indigenous territories. The enterprise has managed to build eco-friendly cabins with local materials in two key areas of the Bolivian Amazon: one on the banks of the Tuichi River in Madidi National Park and the other on the banks of the Yacuma River in the Municipal Protected Area of Pampas del Yacuma, a critical region for the conservation of flooded savannas that is also part of the Amazon basin. The focus of their ecotourism experiences is to welcome nature-loving travelers who seek contact with the rich fauna and flora of the region while minimizing their environmental impact.

Two and a half hours up the Tuichi River by boat from Rurrenabaque – a gateway to Madidi – you will find the nine cabins of Mashaquipe Ecolodge, built with ancestral knowledge in the traditional Amazonian style, with wooden and earthen floors, palm walls, and jatata roofs. One of Wilmar’s greatest dreams and visions is for Mashaquipe to become the leading community-based tourism company in the Bolivian Amazon region.

Mashaquipe Ecolodge in Madidi. Photo: Archive Wilmar.

Its extraordinary biological richness and ecosystems of Madidi harbor 1,830 confirmed species of vertebrates, 5,535 species of plants, 1,809 species and subspecies of butterflies, making it the refuge with the greatest diversity of wildlife confirmed by science.

Despite the significant efforts of Tacana families to conserve the standing forest using tourism as a shield, the central government views tourism as the main obstacle to its large extractive projects on rivers like the Tuichi. Wilmar sees tourism as the perfect symbiosis between sustainable development and conservation, but he acknowledges that the State is not interested in supporting its growth in the area, as it hinders their interests in executing large projects like mining, which poisons the waters, and dams that flood the forest.

The constant insistence of the central government on strangling the river, tearing away the forest’s banks with bulldozers, and devouring Madidi’s natural wealth, has become the main challenge for tourism. Wilmar’s eyes witness how mining activities on the Tuichi are occupying more and more space and, in the process, silently poisoning the river’s flow with mercury – a toxin that now courses through the veins of all communities and animals that depend on its waters.

The mercury poison is no longer a secret to the communities of the Bolivian Amazon. They are the ones who have experienced the symptoms and seek to shout to the world that they are being annihilated with each sip of water and each bite of fresh fish. A study commissioned by the Indigenous Peoples’ Central of La Paz (CPILAP) and analyzing people’s hair reveals grim data: 36 communities in the Beni River basin and its tributaries – the Tuichi, Quiquibey, Tequeje, and Madre de Dios rivers – are being poisoned with mercury. 75% of the evaluated individuals exceed the concentration limit allowed by the World Health Organization (WHO) of 1.0 part per million (ppm) of this toxin, while the rest remain exposed to this contamination. This irreparable damage affects the health of the communities and future generations who live and depend on these now permanently contaminated waters. CPILAP will not stand idly by and has taken measures in pursuit of justice and defense for the affected peoples. On May 19, 2023, exercising its legitimate powers, it held a departmental assembly in the Tsimane Moseten Regional Council (CRTM) TCO, issuing Resolution No. 03/2023, and determining to take legal actions to denounce the impacts caused by gold mining before national and international authorities, declaring the direct damage and violation of indigenous peoples’ rights: health, food, a healthy environment, prior informed consent, territory, and life.

Tuichi River confluence with the Beni River. Photo: Karina Segovia.

Marcos Uzquiano says that mercury also flows through his body, and that the study, despite providing a glimpse of the damage to some indigenous communities, falls short. He assures that when studies are also conducted on the entire urban population of the Amazon, the results will reveal revealing information. He says this because his livelihood has always come from the Tuichi River and its tributaries since birth. His grandmother is of Tacana origin, and he was raised in San Buenaventura, a town on the banks of the Beni River, just in front of Rurrenabaque, one of the entrances to Madidi National Park. He and probably his entire family are also poisoned.

Since he was a child, the forest has always been his source of inspiration—everything green, the landscape—growing up in that environment made him want to care for and protect that living space with all his might before it was even called a national park. For Marcos, the Amazon is a vast living space, and the rivers symbolize that force, that energy of nature, and that connection with the people—a link they have ancestrally used for transportation, movement, and nourishment. The river is more than water; it is a path of encounters.

The force of the river has led Marcos Uzquiano to descend its waters on a raft on several occasions during his time as a park ranger and even before when he worked in tourism. In 2007, he took a course in the United States on Protected Areas, and upon his return, he slowly became interested in rafting, daring to promote the idea. Even before that, he knew that tourists came from Peru to La Paz and then drove to the upper region of the Tuichi to embark on a four-day rafting trip to Rurrenabaque. A whole group of adventurers who longed to repeat the route taken by Jossi Ghinsberg and feel the fury of the river.

Marcos has immersed himself in the river several times, but that doesn’t diminish his desire to talk about it. Listening to the river’s waters roar inspires respect; it’s like hearing the river speak, telling you, «I am here,» and suddenly, you feel how small you are in the face of the power and strength of nature. During his time as a park ranger, he had the opportunity to collaborate with Hayley Stuart, a documentary filmmaker and rafting instructor from the United States. She traveled to Madidi several times to work on a cultural exchange program called «Ríos to Rivers,» with a very special mission: to train young indigenous people in kayaking or white-water rafting, river defense, and documentary making to protect their ancestral lands and the threatened tributaries of the Bolivian Amazon.

Navigating Tuichi River. Photo: Archive Marcos.

Hayley was already aware of the threat of the dam that the government insists on building on the Beni River, and she sought to train local youth in rafting and organize symbolic river descents as a form of protest, but also to showcase the ecotourism potential of free-flowing rivers. In 2007, the Bolivian government declared the Chepete-El Bala hydroelectric project a national priority. Two massive concrete structures—one in the monumental El Bala canyon, where the Tuichi River ends and the Beni River begins, and the other in the narrow Chepete passage, 70 kilometers away from Rurrenabaque—would create two reservoirs: Chepete, covering 677 km², and El Bala, covering 94 km². The combined surface area of both reservoirs would create a vast lake, covering an area five times larger than the urban area of the city of La Paz. The environmental damages are not included in the project’s environmental assessment documents, and it is not of importance to the central government, which insists on proceeding with the project. However, the communities are already aware of the damage, despite some leaders being in favor and others against it. The Federation of Indigenous Communities of the Beni, Tuichi, and Quiquibey Rivers rejects the government’s initiative and takes on the defense of the ancestral territories of the six indigenous nations threatened by the project: the Mosetén, Esse Ejja, Tsimane, Tacana, Leco, and Uchupiamonas, where more than 5,000 people live and depend on the flow of these waters. The impact on the entire Amazon basin would disrupt the reproductive cycle of fish, aquatic biodiversity, and the livelihoods of the communities, upsetting the entire ecosystem dependent on free-flowing rivers.

Angostura of El Bala where they want to build a mega reservoir. Photo: Karina Segovia.

Marcos regrets that before the dam, mining arrived, a subject he often discussed with Hayley and which, just last year, when she returned to evaluate her program, did not allow her to enter the Upper Tuichi due to the presence of illegal mining cooperatives contaminating the Azariamas area.

Being a park ranger and defender has become his identity. Dressing up as a ranger, from head to toe, fills Marcos with pride as he ventures into the forest. With a calm but passionate voice, he recounts his experiences to all who visit him, while navigating the Bolivian Amazon rivers—wearing tall boots, khaki pants, a bag by his side, a hat, aviator glasses, and binoculars, as if he were born for this.

Navigating Normandía Lagoon in the Beni Biosphere and Biological Station (EBB). Photo: Lisa Mirella.

Marcos no longer lives in the Madidi area, but he knows the territory as if it were a part of his body. He worked around the Tuichi for 18 years. During that time, he spent eight years as a park ranger at Madidi National Park, five years as Chief of Protection, and five years as Acting Director. He also spent one month as Acting Director of the Pilón Lajas Protected Area, to the right of the Tuichi River, six months as Chief of Protection of the same area, and another six months in the southern Bolivian Amazon TIPNIS. Throughout his tenure, he fiercely and bravely defended his «big house» (Madidi), to the point that due to his social media denunciations of the constant illegal mining invasion of the Tuichi, he was transferred to another protected area, the Beni Biosphere Reserve and Biological Station (EBB), located at the convergence of three biogeographic regions: the Amazon, the Chaco, and the Cerrado. Another place in the world where Marcos spends his days protecting everything around him.

From his new position, he continues to raise his voice in defense of the Tuichi and Madidi. He apologizes to his followers because lately, he only posts on his social media about the advancement of illegal mining, but he knows that if he doesn’t keep insisting, it will be too late. He considers the Tuichi a key component for the management and conservation of Madidi, being one of the main bodies of water that originates and ends within the national park and also serves as a home to indigenous communities, giving it incalculable cultural value. Upstream, in the upper basin, he recognizes that there are more communities that have been forgotten and are at a higher risk of falling into the clutches of mining. He observes how international cooperation always works with the indigenous people, but it has generated an imbalance. Despite the fact that indigenous communities have been pioneers in community-based tourism, Marcos questions, «What about the rest?» He acknowledges that there are approximately 29 peasant communities higher up in the Tuichi, where the government, instead of promoting sustainable development, encourages the creation of mining cooperatives for work. These cooperatives do not engage in artisanal mining but rather dig the riverbanks with bulldozers, hungry for gold, leaving the water murky and releasing mercury, which flows silently and invisibly downstream, poisoning all the tributaries of the Amazon. Marcos firmly believes that tourism is the best proposal to help save much of what remains of Madidi, but only if there is a fair distribution of resources and opportunities in the region.

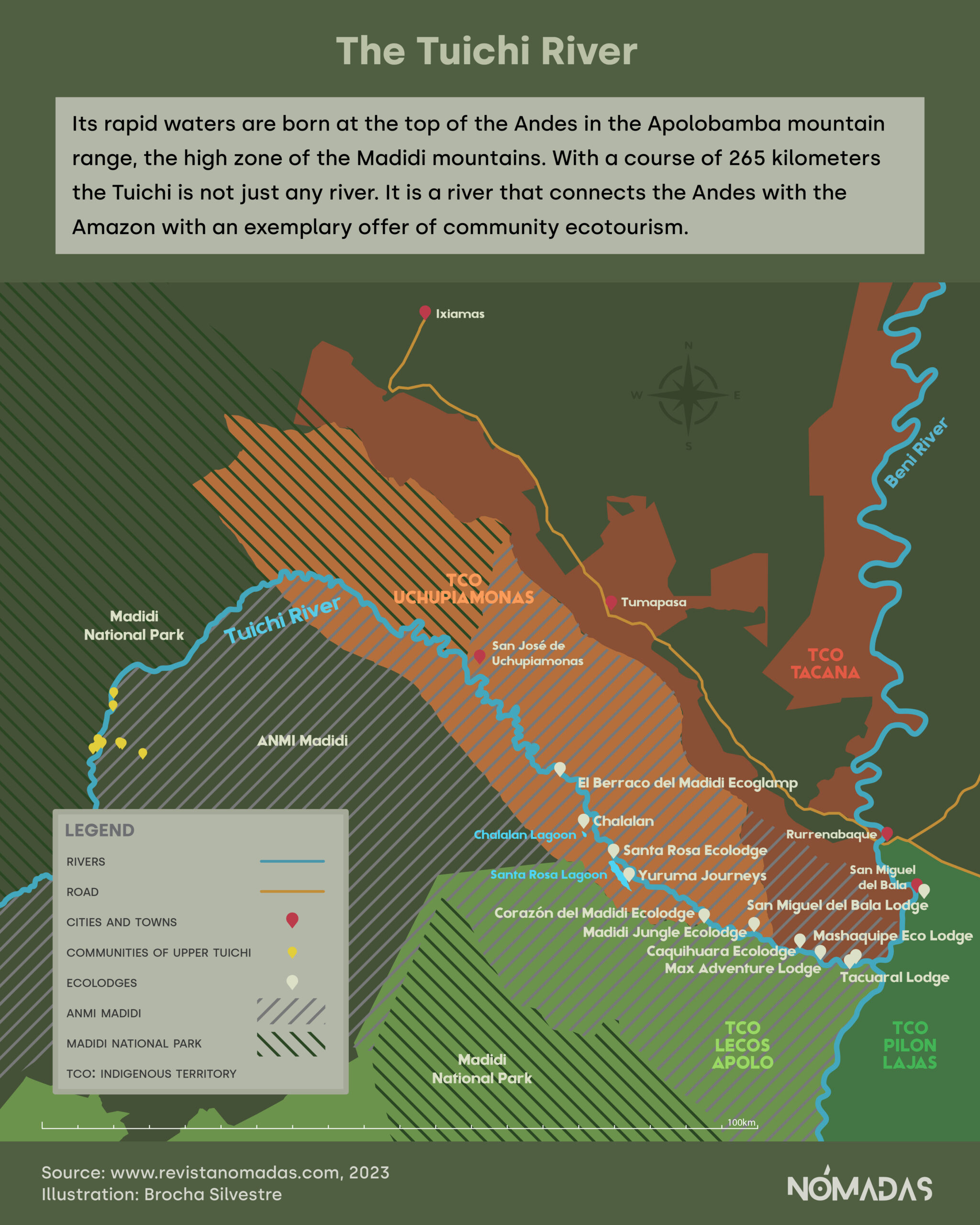

Map of the Tuichi River.

Chalalan, Mashaquipe, and the rafting proposal have become part of the history of protecting the mystical Tuichi River. Now, downstream, it houses a diversity of ecotourism ventures, such as El Berraco del Madidi EcoGlamp, Yuruma Journeys, Santa Rosa Ecolodge, Corazón del Madidi Ecolodge, Caquihuara Ecolodge, Max Adventure Ecolodge, Tacuaral Ecolodge, and San Miguel del Bala. Not to mention Sadiri Lodge, another iconic venture specializing in birdwatching, located in the heart of the humid forest, at the entrance to Madidi via a dirt road. All of them are seeds from Chalalan and the result of the efforts made by indigenous communities, despite the adversities, to build a world for future generations. This wide range of ventures actively works to improve the quality of life for their families, offer environmentally responsible services, and resist the advance of enemies of the world’s most biodiverse forest.

***

This chronicle is part of the Special: Bolivia’s Invisible Amazon and its guardians who do not give up, carried out by Revista Nómadas, with the support of the Amazon Rainforest Journalism Fund in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

STAFF:

DIRECTOR: Roberto Navia. PRODUCTION MANAGER: Karina Segovia. PHOTOGRAPHS: Karina Segovia, Lisa Mirella Corti. SOUND PRODUCTION AND POST-PRODUCTION: Andrés Navia. ILLUSTRATIONS AND INFOGRAPHICS: Brocha Silvestre. SOCIAL MEDIA EDITOR: Lisa Mirella Corti. WEB DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT: Richard Osinaga. COLLABORATION: Manuel Seoane, Diego Adriázola y Daniel Coimbra.

COPYRIGHT 2023

Te contamos desde el interior de los escenarios de la realidad, iluminados por el faro de la agenda propia, el texto bien labrado y la riqueza poética del audiovisual y de la narrativa sonora, combinaciones perfectas para sentir el corazón del medioambiente y de los anónimos del Planeta.